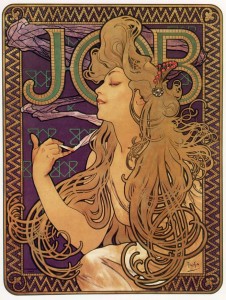

Alphonse Mucha poster 'Job'

The Art Nouveau movement started in the 1890s, drawing its inspiration from nature. Women, flowers and insects were pictured realistically with curved flowing lines that were rarely symmetrical. A poster by the Austrian artist Alphonse Mucha for the cigarette paper “Job” (pronounced “johb”), is a famous and marvelous example of Art Nouveau art.

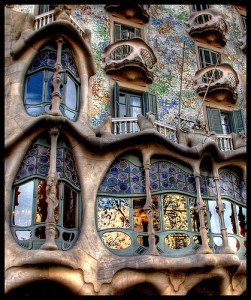

Casa Batlló, a Gaudi building in Barcelona

The Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, was a great proponent of the Art Nouveau movement. His famous buildings still exist in Spain, mostly in Barcelona.

Emile Gallé dragonfly table

In France, the Art Nouveau movement flourished with Emile Gallé at the forefront. He created some wonderful examples in both glass and wood, often incorporating a dragonfly into his work, one of the quintessential symbols of the Art Nouveau period. Sometimes in glass, two similar examples exist, one with and one without a dragonfly. The value can double with the incorporation of a dragonfly into the work. How about two or three dragonflies? Even better.

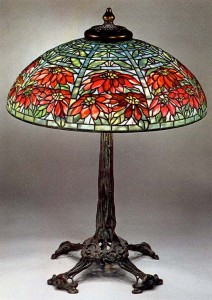

The best examples of Art Nouveau are European, but there are some outstanding American examples, with Louis Comfort Tiffany leading the way.

The Art Nouveau movement started to lose its luster in the teens, when it underwent a transitional period, leading to the Art Deco movement in the 1920s and 1930s. More on Art Deco tomorrow.

Tiffany Studios Double Poinsettia table lamp with fantastic Art Nouveau root base

Please send me your suggestions or questions about art glass, lamps, Louis Icart, shows, auctions, etc. If it’s interesting, I’ll answer your question in a future blog entry.

Call or write and let me know what you would like to buy, sell, or trade. philchasen@gmail or 516-922-2090. And please visit my website. chasenantiques.com