Most Icart etchings that are in original frames with original mats have problems, such as foxing, light darkening, glue or acidity, amongst others. Read yesterday’s blog for a more complete explanation.

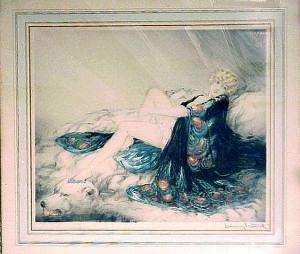

Icart "Lady of the Camelias", with original frame and mat

Some people like them that way. They show their age (usually 70-90 years old). They’re probably authentic (it’s difficult to fake the brittleness and other signs of age). They have character, with nicks in the frame and faded mats. The problem is they’re getting worse, year after year. The degradation continues with constant exposure to high acid levels, bright light and humidity. Remember the value is in the etching itself, a sheet of paper. It’s the cake, while the mat and frame are the frosting. Good restorers are capable of reversing most of the damage that’s accrued in almost a century.

The process starts by removing the etching from the frame. That’s pretty simple. There is usually a paper backing that can be torn off. (It can’t be reused so it doesn’t matter if you tear it off.) Below that is the backboard. That’s usually held in with many nails around the perimeter on older frames. Later frames may have framing points. Either one can be removed with a flat screwdriver and a needle nose pliers.

Framing points

Then the backboard is removed to get to the etching underneath. Depending on the technique of the original framer (and they had many different styles), the etching may be a loose sheet that’s taped on the top or the edges (that would be the best). Usually the etching is found within a glue sandwich — glued to the board in the back and the mat in the front. Every variation is possible — the etching may be glued only to the mat in front, or only to the board in the back or only glued around the edges or best of all, no glue at all.

The restorer then puts the etching in a full bath and begins the process of separating the paper from anything it’s glued to and then to removing the glue itself. Sometimes the glue softens and the job of removal is facilitated, but on occasion the glue is tenacious and removal becomes a very labor intensive and time-consuming process. It’s very easy to damage a soaking wet etching, so this job should be left to a professional.

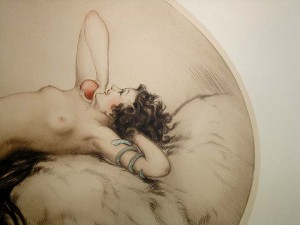

Once the sheet has been freed, a chemical process is started that in most cases can reverse most of the effects of aging. (Sounds wonderful to me. I’d like to get dipped myself and see if I can reverse the effects of aging.) If it’s done properly, the foxing can be eliminated and the light darkening and acid burns can be reversed. The etching is then thoroughly washed, which eliminates most of the acid. A buffering solution can be added to slow down future acid buildup and finally the etching is dried in a press. Most of the hand-painted details like lipstick are lost in the restoration process and have to be reapplied by hand.

Now the etching is a loose sheet that looks almost as good as the day it was made. It’s ready to be framed properly by modern standards. That means that non-acidic materials are used in the framing and mounting. Rag mats are made of cotton and are pH neutral (A pH of 7 is neutral). Anything that comes in contact with the etching either is acid-free or separated by an acid-free barrier. With proper conservation and framing, your etching will look great and last for many more years.

Contact me if you have an etching that needs conservation.

Please send me your suggestions or questions about art glass, lamps, Louis Icart, shows, auctions, etc. If it’s interesting, I’ll answer your question in a future blog entry.

Call or write and let me know what you would like to buy, sell, or trade. philchasen@gmail or 516-922-2090. And please visit my website. chasenantiques.com