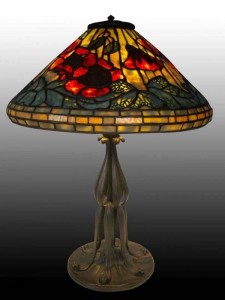

Steuben Tyrian vase (not the one from this story)

In the early 1990s, during a difficult recession, I was exhibiting at a show at the New York Coliseum. For the first couple of days, the dealers were setting up the show, walking around and buying from each other — normal procedure for any show. I came to the booth of a dealer who had sold me many things in the past. He had broad knowledge of a diverse range of antiques. He was the kind of dealer who could go into someone’s house and feel just as comfortable buying an oriental rug, or a painting or a Tiffany lamp. He had a vase on the table that I recognized right away without picking it up. I asked him the price and he replied that it was signed something on the bottom that he couldn’t read and because of it, the price was $1500. I bought it, brought it back to my booth and put it under the table.

The vase was a Steuben Tyrian vase, which has a characteristic look. Steuben signed these vases “Tyrian”, but not Steuben. The wear on the bottom of the vase was considerable, so the scratches through the word Tyrian made it very difficult to read, unless you already knew what it said.

The next day, I called Roger Early in Cincinnati and asked him if he would like it for his next auction. He told me his deadline was coming up very soon, but that I could make it on time if I would send the vase to him overnight, which I did. He called me the next day to tell me that if I didn’t want to take the risk at auction that he would write me a check immediately for $6,000. (Now why would I want to do that?) I knew the vase had the potential to bring substantially more, so I told him to just put it in the auction and let it sell. The result? $13,000.

- Knowledge is power. Sir Francis Bacon, Religious Meditations, Of Heresies, 1597.

If you like my blog, please recommend it to others. Email me with your comments. philchasen@gmail.com